Upstairs, Downstairs at Mr. Paca’s House

By Nancy Breslau Lewis

The symmetrical brick façade of the mid-18 th century home of William Paca rises above Prince George Street , its stately Georgian architecture still referencing Paca's position as one of Annapolis 's most prominent movers and shakers during the Revolutionary period.

Born near Abington in 1740, in what is today Hartford County , William Paca was in many ways to the manor born. After being tutored in the classics at home, he went on to study at the College of Philadelphia (later known as the University of Pennsylvania ) and read the law in Annapolis —not surprising, since his father was a member of the colonial legislature. William, too, had political aspirations and enjoyed a thriving law practice.

All this made him quite the eligible young bachelor and in 1763 when he married Mary Chew, a well-connected Annapolis heiress a few years his senior, it was considered a very good match indeed. Four days after their marriage, Paca purchased two adjacent one-acre lots between Prince George Street and King George Street . Perhaps with the help of an unknown architect or experienced building contractor, Paca oversaw the construction of his home and its elaborate formal gardens over the next couple of years.

During the 15 years he resided in the house, Paca became increasingly involved in the roiling politics of his day. In 1774, he attended the First Continental Congress and later signed the Declaration of Independence, one of four Maryland signers. (Interestingly, homes associated with all of Maryland's signers still remain intact and are to be found within a few blocks of each other in Annapolis's historic district—a rare architectural legacy.)

In 1778, Paca became Chief Justice of the State Superior Court, and he sold his Annapolis home two years later. He went on to become a three-term governor and subsequently was appointed to a federal district court judgeship by George Washington. He served in that position until his death in 1799.

Yet during the period of Paca's great political success, many sorrows beset the family living on Prince George Street . When Alexandra Deutsch became curator of the William Paca House and Garden museum three years ago, she made it her mission to train a spotlight on the personal lives of the house's occupants. Beneath the trappings of a wealthy family—expressed by the home museum's impressive collection of 18 th -century furniture and artifacts—lay a compelling human story.

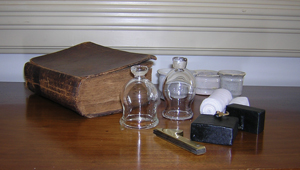

“Our recent reinstallations [of artifacts] have allowed people to connect with the house, and not simply view the Paca household as “an heiress, a patriot and the servants who took care of them,” Deutsch notes. A second story bedroom, for example, has been reinstalled as a “sick room” where Paca children and relatives were nursed. In one three-year period during the 1760s, numerous deaths occurred in both the Paca and Chew families, including that of little Henrietta Maria Dorsey (“Henny”), Mary's orphaned niece, who had come to live at the Prince George Street mansion not long after Mary may have buried one of her own children. Henny died less than ten months later. As it's presently refurbished, however, the house's “sick room” focuses not on her death, but on the ministrations she most likely received during her illness. An 18 th -century medicine chest sits on a table, replete with vials used to contain such medicinals as camphor for rashes and respiratory ailments, sassafras and licorice for calming stomachs, and digitalis for heart problems. Cups and blades used for bleeding and blistering (thought to be curative) and bandages are also on display.

A silver pap boat, used to tip thin gruel or beef tea into an invalid's mouth, rests on the rope bed. Even more poignant are the small chair and table placed bedside. There, a caring slave—likely Bett, one of the slaves known to have lived with the Pacas—would have hovered over her patient. On the table can be seen a facsimile of the kind of food likely to be served to a favored household servant: fatback pork, vegetables, a chicken leg and even a roll made of white bread (albeit slightly crushed, a reject from the Paca's dinner fare).

Downstairs in the kitchen, a kind of hierarchy among the African-American slaves living in the Paca household becomes even more apparent. A plate holding simple brown bread and beans, with plenty of hominy, rests on a table, perhaps left by a slave who's gone out to draw water, or empty chamber pots from the upstairs bedrooms or ashes from the hearth. Thin mattress ticks, made of simple striped cotton and stuffed with corn husks or straw, lie rolled up against the wall. This was as soft a night's sleep as most of the eight to ten slaves that lived in the house could expect to enjoy. By artfully using quotidian objects, the staff at Paca House has succeeded in conveying the material presence of the African-American slaves who lived, labored and loved in William Paca's house.

The cooking utensils arranged about the kitchen reveal just how labor-intensive 18 th -century food preparation was. Even boiling a pot of water could take an hour. The showstopper of the kitchen's entire installation of cookware is the clock jack, an extremely expensive kind of mechanized spit that was sold down at City Dock during the colonial period. “It was the Viking stove of its time,” Deutsch remarked. Such tools for hearth cooking were necessary in households like the Pacas', where high-style dining involved three-course meals of eight to ten dishes per course.

Evidence of the wealthy family's pride in producing epicurean meals is displayed in the “formal” dining room upstairs. Platters of candied ginger, an almond cake shaped like a hedgehog, brightly colored gelatins called “ribband jellies”, candied violets and sweetmeats and elaborate blancmange custards bedeck the table. Such a spread not only represented many hours of labor but an equally impressive outlay of money. Refined sugar and flour were dear and expensive brass cooking pots and copper molds (on view in the kitchen below) had to be purchased to whip up and mold creamy deserts.

Although the dining room's English mahogany table laden with elegant displays clearly impressed, it was the formal parlor at the front of the house, with its Prussian blue walls, elaborate plaster work and sophisticated furnishings, that functioned as “the epicenter of the highest level of socializing,” according to Alexandra Deutsch. As she explains, “When the room was unoccupied, the doors were kept locked. It's not a place where everybody would have been invited in.”

None of the period card tables, chairs and sofa within the room are original to the house, although all of the loaned, purchased and donated antiques have been carefully researched and found to be typical of those owned by an elite Chesapeake family of the period. Just three years ago an Annapolis-made tall case clock was purchased at auction for upwards of $80,000 and installed in the parlor. Arguably the Paca House museum's jewel in the crown, the clock dates to around 1772 and was created by master craftsmen William Faris, Archibald Chisholm and John Shaw. Fundraising is underway to come up with the $50-60,000 necessary to fully conserve the clock case and horological works.

From elegant to earthy, the exhibits at the William Paca House and Garden capture the texture of life as it was lived in Annapolis nearly two and a half centuries ago. Since the house museum is open Monday through Saturday from 10 am to 5 pm, and from noon to 5 pm on Sunday, you'll have ample opportunities to explore this Annapolis landmark. Back

|