A New Look

For an Old Master

By Douglas Lamborne

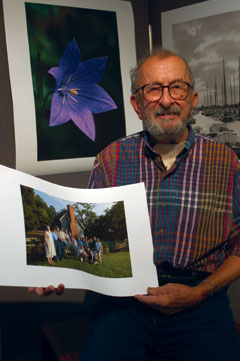

Marion E. Warren is 84

and has had more than his share of physical afflictions, the ideal

specimen for a rocking chair on the porch or a nursing home. But

no. There's work still to be done. Almost daily, he makes his

way through the clutter of his basement to his darkroom, as he

has for more than a half-century, to work on his photographs.

And when he is done there he moves over to his light table to

take on the gargantuan chore of editing thousands of color transparencies.

Yes, those are color transparencies by M.E. Warren, whose black

and white images hang in the State House, in countless dentists'

offices, on city buses, and over mantles across the region.

In order to appreciate this current busyness we need to take a

cursory look back. Warren took up photography at the age of 17

and soon found work in studios in St. Louis. He was a photographer

while in the Navy during World War II and served in Washington

where he met Mary Giblin, who would become his wife.

He continued to move east, to Annapolis in 1947, where he set

up shop, covering weddings and then taking on commercial assignments.

At the same time his artistic eye focused on the variety of life

in Maryland, especially life on and around the Chesapeake Bay.

Photo shoots grew into collections, collections into books.

His second book, The Train's Done Been and Gone: An Annapolis

Portrait 1859-1910, produced with daughter Mame, was published

in 1976. It comprised photos of long-ago Annapolis that the Warrens

begged, borrowed and otherwise wheedled from private collections.

Many of these photos almost certainly were retrieved from oblivion-or

worse.

The book showed several things about Warren: his concern for historical

images and his eye for the everyday-ness of life.

The book showed several things about Warren: his concern for historical

images and his eye for the everyday-ness of life.

Both were evident in the massive body of his own work, which in

1987 he donated to the Maryland State Archives, a treasure trove

of more than 100,000 black-and-white negatives.

His next chore was the Bay Project, an intensive look at the Chesapeake,

which resulted in his seventh book, again in black and white,

Bringing Back the Bay, published in 1994 and reprinted

in 2002.

Trouble piled up for Warren as the millennium approached. His

own physical problems increased, and wife Mary slipped into the

ever-gathering darkness of Alzheimer's, which ultimately claimed

her last year.

Despite the hurdles, an exhibit of Warren's work was mounted in

2001 at the Mitchell Gallery at St. John's College. The show's

opening night was a mob scene, suggesting some sort of valedictory.

Not so. As usual, there was more work to be done.

In the hubbub attending that show Warren met Joanie Surette, a

graphic designer. The two agreed to talk, and Surette showed up

for the chat with some vine-ripened tomatoes grown on the South

County farm where she lives. The tomatoes, both agreed, helped

to seal the deal, a collaboration that led to her becoming his

business partner.

"It was one of those meetings where I think we both knew instinctively

that we could work well together," she says. He concurs: "Something

told me she and I would click. She knew how to adapt very quickly.

This was always a problem for me with people who have worked for

me in the past. I trust Joanie's judgment completely."

Surette brought order to the day-to-day running of the enterprise,

including an increase in the price of his images. Warren's eyebrows

still arc in wonder at the cost of his photographs today. (Two

photographers interviewed for this story said the price rise was

long overdue.)

Surette freed up Warren to continue working in the darkroom. He

discovered gradually that he had a new problem: the steady demand

for certain of his photographs was causing his negatives to become

damaged or scratched. He noticed it first in his moonlit image

of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, an iconic M.E. Warren photograph

taken in 1953. And if that weren't enough, he was coming to realize

that the high-quality paper he had been printing on-essential

for that archival look-was becoming less available.

Surette freed up Warren to continue working in the darkroom. He

discovered gradually that he had a new problem: the steady demand

for certain of his photographs was causing his negatives to become

damaged or scratched. He noticed it first in his moonlit image

of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, an iconic M.E. Warren photograph

taken in 1953. And if that weren't enough, he was coming to realize

that the high-quality paper he had been printing on-essential

for that archival look-was becoming less available.

"A lot of people don't know that many photographers don't print

their own work," says Surette. "Marion is a master printer as

well as a master photographer." What was to be done?

A principal at the Packard Reath Gallery in Lewes, Del., two years

ago connected Warren with Richard Olsenius of Annapolis, photographer

and printer. It became a collaboration good for both.

Olsenius is a former news photographer from Minneapolis who became

a subcontractor and staffer with National Geographic. Early on,

he had an interest in large-format printing and computers, eventually

combining the two. "A tremendous new set of tools had emerged,"

he says of those early computer days. "And I chose to embrace

it."

When the National Geographic got serious about digital, Olsenius

was invited to Washington. (He and wife Christine went further

east to settle in Annapolis.)

The first Warren negative Olsenius worked with was the Bay Bridge

shot. "I'm not adding or subtracting anything," he says. "These

new tools mean I am able to work more precisely burning and dodging.

It's simply better printing."

Burning and dodging is what the photographer does in the darkroom,

massaging his prints under the dim yellow lights. The process

Olsenius uses brings out detail in negatives that had never seen

the light of day.

Asked to simplify an explanation of what he does, Olsenius offers

this: "Rather than projecting an image on a paper coated with

a silver compound, we're spraying an image on with ink. The traditional

process goes through this chain: eye to camera to film to enlarger

where the image is projected onto silver gelatin. With this digital

process it's the eye to camera to chip to computer, which acts

as the enlarger, to the printer, where it's sprayed."

The procedure was painstaking for both. "He'll do a proof and

I will say do this or do that," says Warren. "It's a very time-consuming

process. You have to go over each print one at a time."

The procedure was painstaking for both. "He'll do a proof and

I will say do this or do that," says Warren. "It's a very time-consuming

process. You have to go over each print one at a time."

"About 10 hours into the Bay Bridge picture I almost gave up.

I thought I couldn't do it," says Olsenius. But he persisted;

it took 22 hours to make it right. "Now, I think I know what he

wants in his prints. Ultimately, the final call resides with him.

There's a lot of back-and-forth, a real collaboration."

He worked on a number of images, using archival paper essential

to his process, paper that also satisfies Warren's demands.

"Marion's been a remarkable shot in the arm for all of us involved

with him," says Olsenius. "Certainly for me. He keeps raising

the bar, showing you can be creative well into your 80s. He proves

to me that the creative drive does not have physical limits. I

think this work has rejuvenated him. It certainly has rejuvenated

me."

After restoring a number of his classic black-and-whites, Olsenius

took on some of Warren's color.

"I've been shooting color all along," says Warren, "since the

1940s." The color that saw the light of day over the decades was

usually commercial work. "I was never satisfied with the quality

of the printing process," he says of his artistic images. Olsenius

has changed that. In the last year some of his color has been

shown at Packard Reath and at DeMatteis Gallery on West Street.

"I didn't think he would get the same reaction with the color

as he has for the black and white," says Bobbie DeMatteis, who

offers Warrens in all hues. "But he has. The color has been accepted

quite well."

The Washington Post Magazine did a cover story on Marion Warren

in 2002 and entitled it "Almost Famous." The article addressed

a touchy matter, the Warren legacy. He has never been the sort

to toot his own horn-he's too nice a guy for that. And he certainly

isn't going to hire someone to do the tooting for him. His work,

some feel, speaks for itself. Eloquently.

There is gathering evidence that his art is not only going to

endure, but become essential. Take, for example, his Chesapeake

Bay work-skipjacks in the morning mist, fleets of workboats tied

up at City Dock, hand tongers scraping for oysters. These images

are vanishing fast. Decades down the road, if you want to find

out what the Bay was like back then, you would go to photographs

by M. E. Warren.

DeMatteis says it is happening now: "A lot of my customers tell

me they realize that what was captured in these images is gone

or soon will be."

Back

|